Share Album:

Centennial

Shelley Washington composer

Gemma Peacocke composer

Amanda Feery composer

Fanny Mendelssohn composer

José Antonio Zayas Cabán saxophone

New from Navona Records is saxophonist José Antonio Zayas Cabán’s CENTENNIAL, an album of cutting-edge solo and chamber music reflecting on the shortcomings of the 19th Amendment during its 100-year anniversary. Rather than celebrating, this album urges listeners to recognize the significant work that remains in achieving global equality.

Zayas Cabán, the central collaborator and performer on Centennial, merges the musical and the political. As a native Puerto Rican and 2020–2021 McKnight Fellow, he works to develop musical projects and collaborations that confront current events and social issues.

As historian Katheryn Lawson and contributors to this album describe, Shelley Washington’s BIG Talk opens from a place of exasperation and power, speaking out against the wide spectrum of rape culture. The “unrelenting, churning duo” between baritone saxophones urges listeners to “stop perpetuating rape culture by any and every means necessary.” Gemma Peacocke’s Skin takes a New Zealander’s view on the ways the U.S. was built and is constantly remade from the illogics of race. Author of the CENTENNIAL opening essay, Lawson states, “anxieties about sexuality between races, between and among genders, are endemic to this system.” This piece for alto saxophone and electronics “[wends] between the intricate layers of privilege, power, and shame associated with race and sex, down into the dark roots of the country’s history.”

Amanda Feery’s Gone to Earth responds to the present moment through the lens of Mary Webb’s novel of the same name. The phrase “gone to earth” refers to foxes hiding in a hunt, an apt metaphor for the ways women are “hunted” in patriarchal societies. Feery was “stunned that [the novel] was written in 1917, and angry that the notion of the predatory hunt and desire to control women is still very much a threat to women’s lives today.” Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel has long been a source of inspiration for those in search of female musicians and composers. A musical prodigy who struggled against patriarchal expectations, she premiered the Piano Trio in D minor in one of her Sunday afternoon musical gatherings, a socially acceptable way for a woman to perform at that time.

By featuring four powerful composers, CENTENNIAL urges listeners to reflect on the false promises of the past and the present. And to fight for better.

Listen

Stream/Buy

Choose your platform

"CENTENNIAL unites the experiences of women, on and off the music scene, in the 19th and 21st centuries"

Track Listing & Credits

| # | Title | Composer | Performer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Big Talk | Shelley Washington | Shelley Washington, baritone saxophone; José Antonio Zayas Cabán, baritone saxophone | 10:45 |

| 02 | Skin (Version for Alto Saxophone & Electronics) | Gemma Peacocke | Gemma Peacocke, electronics; José Antonio Zayas Cabán, alto saxophone | 7:02 |

| 03 | Gone to Earth (Arr. for Soprano Saxophone, Tenor Saxophone & Piano) | Amanda Feery | Casey Rafn, piano; Ryan Smith, tenor saxophone; José Antonio Zayas Cabán, soprano saxophone | 7:17 |

| 04 | Piano Trio in D Minor, Op. 11 (Arr. for Soprano Saxophone, Tenor Saxophone & Piano): I. Allegro molto vivace | Fanny Mendelssohn | Joel Gordon, tenor saxophone; Casey Rafn, piano; José Antonio Zayas Cabán, soprano saxophone | 11:26 |

| 05 | Piano Trio in D Minor, Op. 11 (Arr. for Soprano Saxophone, Tenor Saxophone & Piano): II. Andante espressivo | Fanny Mendelssohn | Joel Gordon, tenor saxophone; Casey Rafn, piano; José Antonio Zayas Cabán, soprano saxophone | 5:37 |

| 06 | Piano Trio in D Minor, Op. 11 (Arr. for Soprano Saxophone, Tenor Saxophone & Piano): III. Lied. Allegretto | Fanny Mendelssohn | Joel Gordon, tenor saxophone; Casey Rafn, piano; José Antonio Zayas Cabán, soprano saxophone | 1:31 |

| 07 | Piano Trio in D Minor, Op. 11 (Arr. for Soprano Saxophone, Tenor Saxophone & Piano): IV. Allegretto moderato | Fanny Mendelssohn | Joel Gordon, tenor saxophone; Casey Rafn, piano; José Antonio Zayas Cabán, soprano saxophone | 5:41 |

All pieces recorded in the Recital Hall at the Voxman School of Music, University of Iowa in Iowa City IA

Recording years: BIG TALK (2017), Trio, Op. 11 (2018), SKIN (2019), GONE TO EARTH (2019)

Recording Engineer James Edel

Special Thanks Mitchell Toebben

Liner Notes Katheryn Lawson

Dedication Rosa Castro Muñiz

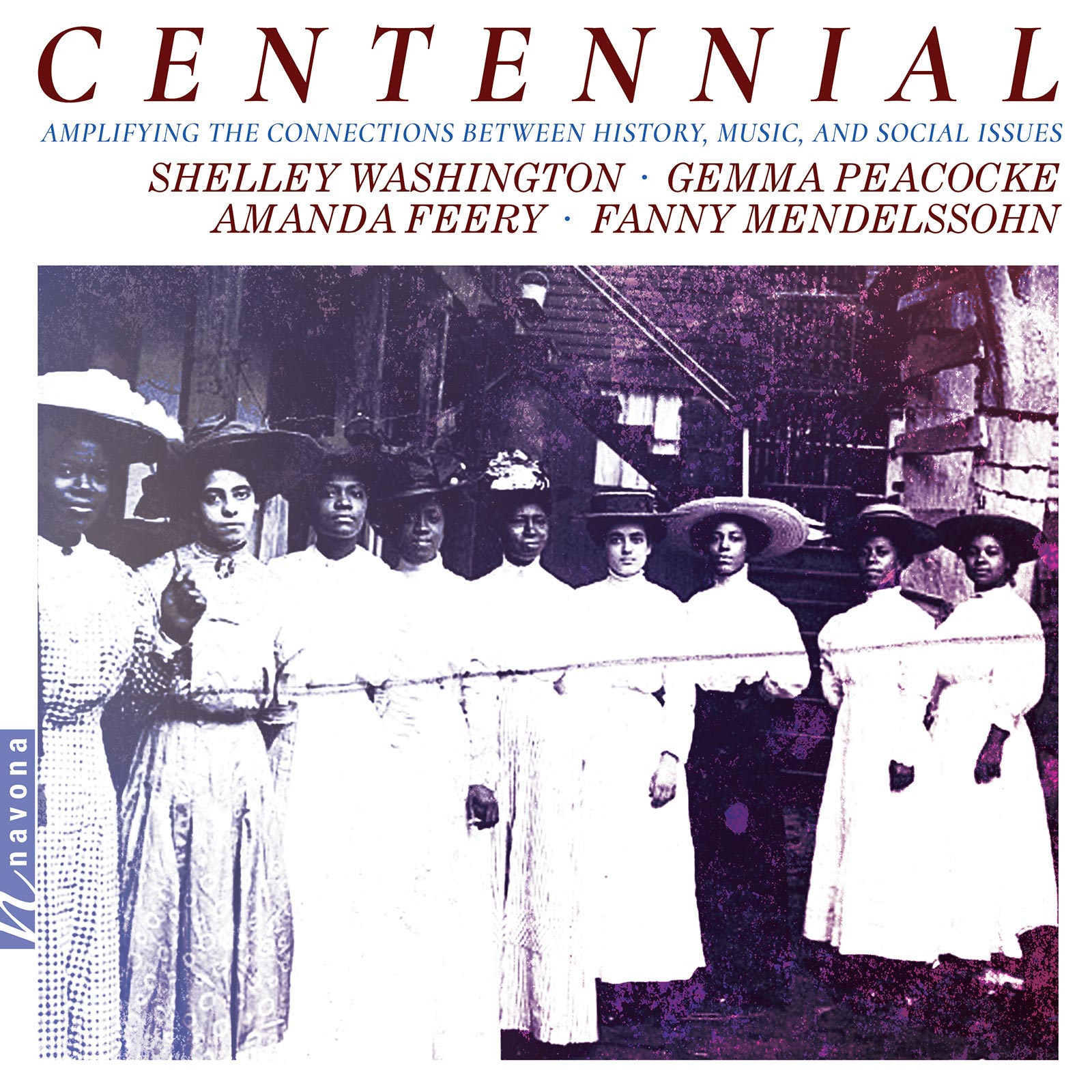

Cover image: Banner State Woman’s National Baptist Convention, ca. 1905-15, Library of Congress.

Executive Producer Bob Lord

Executive A&R Sam Renshaw

A&R Director Brandon MacNeil

A&R Jacob Smith

VP, Audio Production Jeff LeRoy

Audio Director Lucas Paquette

VP, Design & Marketing Brett Picknell

Art Director Ryan Harrison

Design Edward A. Fleming

Publicity Patrick Niland, Sara Warner

Artist Information

Gemma Peacocke

Composer Gemma Peacocke grew up in Hamilton, New Zealand, and she moved to the United States in 2014. She writes a broad range of music including art-pop songs, EDM-inspired tracks and orchestral music. She has a particular love of interdisciplinary work and often collaborates with artists, writers, and theatre designers.

José Antonio Zayas Cabán

A Grammy-nominated artist and McKnight Fellow, José A. Zayas Cabán has presented performances and taught master classes throughout Europe, the Caribbean, and North America. A native Puerto Rican (born and raised in Mayagüez PR) and musician activist, José now resides in Minneapolis MN and is building an artistic career focused on developing projects, albums, and collaborations that address, respond, and raise awareness about current events and social issues.

Shelley Washington

SHELLEY WASHINGTON writes music to fulfill one calling: to move. Described as having the ability to “expertly mine the deep wells of private emotion,” (Steven Jude Tietjen, Opera News) she uses driving, rhythmic riffs paired with indelible melodies to create a sound dialogue for the public and personal discourse.

Amanda Feery

AMANDA FEERY is an Irish composer working with acoustic, electronic and improvised music. Much of her inspiration comes from literature, folk musics, cultural criticism, and the natural world.

Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel

(1805, Hamburg [Germany] – 1847, Berlin, Prussia) was a German pianist and composer, the eldest sister and confidante of the composer Felix Mendelssohn.

Joel Gordon

Born in Iowa, grown in Missouri, and sprouting through the Midwest, Joel Gordon is a cultivating saxophonist and music educator. As a musician and teacher, Gordon strives to balance life on “both sides of the fence,” playing in concert classical and jazz contemporary circles.

Casey Rafn

CASEY RAFN is active as a freelance pianist in the United States and abroad. As a collaborative pianist, he has performed at venues in Canada, Latin America, New York, and across the United States.

Ryan Smith

Multiple woodwind specialist Ryan Smith is drawn to music from many different genres, regularly performing in Iowa and throughout the Midwest with symphony orchestras, chamber ensembles, jazz combos, musical theater pit orchestras, and rock bands.

Notes

The 100-year anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment feels like some kind of cause for celebration. But here, in this space, with these words and the sounds you’ll hear, we are not celebrating. This is a time to reflect on the false promises of the past and the present. And to fight for better. The 1920 amendment to the U.S. Constitution proclaimed that “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” White women enjoyed these rights long before women of color. The so-called rights of Black suffrage provided by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments (1868 and 1869) were regularly undercut by state and local practices like poll taxes, literary tests, and the grandfather clause. After 1924, when the U.S. severely limited migration through the quota system (the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act), citizenship was filtered through whiteness. In the historic case Ozawa v. United States (1922), Japanese were legally categorized as non-white, as other. Queer bodies were stopped at the nation’s many borders and outposts for fear of these persons “likely” becoming a “public charge.” Poll taxes and other forms of suppression were outlawed in the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which also created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Indigenous tribes and nations continue to experience the ebb and flow of federal recognition, itself a contentious form of legitimacy. No. This is not a time for celebration.

I list these dates, yes, as a history lesson, but also to force us to see, hear, and feel the ways that these histories endure in the present. The bell of inequality, of the U.S.’s settler colonialism, was rung long ago. And it has yet to go silent. This project came to fruition in the midst of the Coronavirus pandemic. This historical and epidemiological moment revealed the harsh truths that many already knew. Asians and Pacific Islanders (American and not) faced new (but unoriginal) waves of racism, as China shouldered the blame for the virus. Disease supposedly doesn’t discriminate, but the health system does. Deaths among African Americans, Indigenous nations, Latinos, and migrants soar above white deaths. As Shay-Akil McLean—a Black transman and PhD candidate in Ecology, Evolution and Conservation Biology—so aptly articulated in 2017, “settler colonialism is the pre-existing condition.” White men wield assault rifles in their own stilted “civil rights” protest because they expect so-called expendable populations to deliver their God-given right to haircuts. No. This is not a time for celebration.

– Katheryn Lawson