Music for Virginal

William Tisdale composer

Charles Metz virginal

Navona Records proudly presents TISDALE VIRGINAL BOOK from harpsichordist and early keyboard specialist Charles Metz. The album features historical repertoire seldom heard even by Early Music aficionados, all performed on a painstakingly restored Francesco Poggi virginal built c. 1590. The virginal, a member of the harpsichord family, was popular in the late Renaissance into the early Baroque period. Metz opts to tune the virginal to A=406 Hz, rather than the modern A=440 Hz as the lower pitch allows for better resonance and tonal quality. He also uses the historically accurate quarter-comma meantone tuning which highlights the consonance and dissonance of the harmonies. Music from composers including William Tisdale (late 16th century), William Byrd (c. 1540 – 1623), John Dowland (1563 – 1626) and Thomas Morley (1557/8 – 1602) is featured on this lovingly-prepared album. Early Music enthusiasts will appreciate Metz’s careful attention to detail as he guides listeners through this centuries-old repertoire.

Listen

Stream/Buy

Choose your platform

"Offers a private and relaxing listening experience"

Track Listing & Credits

| # | Title | Composer | Performer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Pavana in G Minor, FVB 220 | William Tisdall | Charles Metz, virginal | 2:42 |

| 02 | Paul's Wharf, TVB 17 | Anonymous | Charles Metz, virginal | 1:33 |

| 03 | John Holmes' Pavan - Robin Smart's Delight, TVB 20 | Anonymous | Charles Metz, virginal | 2:16 |

| 04 | Pavan, TVB 19 | Robert Johnson | Charles Metz, virginal | 3:36 |

| 05 | Medley, TVB 1 (Arr. W. Randall for Virginal) | [Edward] Johnson, arr. William Randall | Charles Metz, virginal | 3:36 |

| 06 | Pavan, TVB 15 (Arr. Heyborne for Virginal) | Thomas Morley, arr. Mr. Heyborne | Charles Metz, virginal | 4:57 |

| 07 | Galliard, TVB 16 (Arr. for Virginal) | Thomas Morley, arr. Anonymous | Charles Metz, virginal | 2:14 |

| 08 | Lachrymae Pavan, TVB 2 (Arr. for Virginal) | John Dowland, arr. Anonymous | Charles Metz, virginal | 3:00 |

| 09 | Passamezzo Pavan, TVB 10 | Anonymous | Charles Metz, virginal | 2:40 |

| 10 | Passamezzo Galliard, TVB 11 | Anonymous | Charles Metz, virginal | 2:07 |

| 11 | Susanne un jour, TVB 12 (Arr. for Virginal) | Lassus, arr. Anonymous | Charles Metz, virginal | 6:47 |

| 12 | Galiarda in D Minor, FVB 295 | William Tisdall | Charles Metz, virginal | 2:26 |

| 13 | Pavan, TVB 6 | John Marchant | Charles Metz, virginal | 1:42 |

| 14 | Coranto, TVB 3 | William Tisdale | Charles Metz, virginal | 1:07 |

| 15 | Lachrymae Pavan, TVB 9 (Arr. W. Randall for Virginal) | John Dowland, arr. William Randall | Charles Metz, virginal | 6:19 |

| 16 | Galliard, TVB 7 "Can She Excuse" (Arr. for Virginal) | John Dowland, arr. Anonymous | Charles Metz, virginal | 1:51 |

| 17 | Pavan, TVB 13 | William Byrd | Charles Metz, virginal | 5:36 |

| 18 | The Hunt's Up, TVB 8 | William Byrd | Charles Metz, virginal | 6:53 |

| 19 | My Desire, TVB 18 | Anonymous | Charles Metz, virginal | 1:18 |

| 20 | Almand in A Minor, FVB 213 | William Tisdall | Charles Metz, virginal | 1:58 |

| 21 | Passamezzo Pavan | Thomas Morley | Charles Metz, virginal | 2:58 |

| 22 | Newman’s Pavan | William Randall | Charles Metz, virginal | 3:46 |

| 23 | Pavana Chromatica Mrs. Katherin Tregians Paven | William Tisdall | Charles Metz, virginal | 4:55 |

| 24 | Pavana Clement Cotto | William Tisdall | Charles Metz, virginal | 1:43 |

| 25 | Coranto | William Tisdale | Charles Metz, virginal | 1:20 |

Recorded 2020 at University of California at Santa Cruz, Music Center Recital Hall in Santa Cruz CA

Recording production, engineering, editing and mastering David V.R. Bowles, Swineshead Productions, LLC

Instrument photos Nicolas Whitman

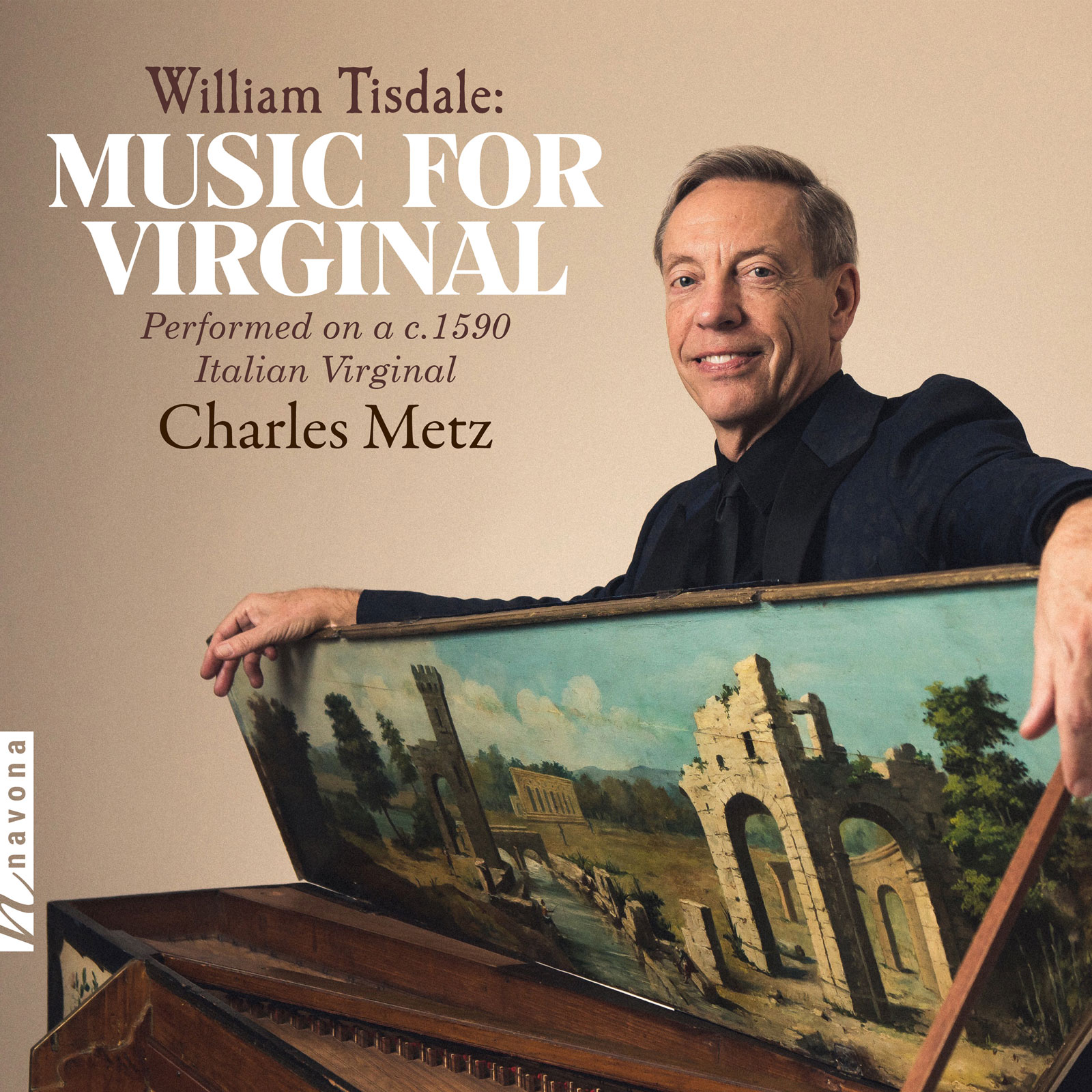

Cover photo Joe Mazza, brave lux inc bravelux.com

To Randy Ford and Richard Ashburner for their love and encouragement

Executive Producer Bob Lord

Executive A&R Sam Renshaw

A&R Director Brandon MacNeil

A&R Morgan Santos

VP, Audio Production Jeff LeRoy

Audio Director Lucas Paquette

VP, Design & Marketing Brett Picknell

Art Director Ryan Harrison

Design Edward A. Fleming

Publicity Patrick Niland, Sara Warner

Artist Information

Charles Metz

Charles Metz graduated from Penn State University with a B.F.A. in piano. Following graduation, he began private harpsichord lessons under the legendary Igor Kipnis. He continued his harpsichord studies with Trevor Pinnock while earning a Ph.D. in Historical Performance Practice at Washington University in St. Louis. More recently, Metz has worked with Webb Wiggins and Lisa Crawford at the Oberlin Conservatory. He has performed solo recitals at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, Oberlin Conservatory, University of Michigan, and Penn State University in State College PA. He has appeared with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, Kansas City Baroque, and the Newberry Consort of Chicago.

Notes

This special recording features an historical repertoire seldom heard, even by Early Music aficionados. But more remarkable, the instrument heard here dates to the years when this music was first played. Nothing is known of this instrument’s provenance before 2005, when it surfaced in an antique shop in Fairview Heights IL. Guided to the shop by a friend, Charles Metz purchased it, following a gut instinct that it was original. Unplayable, the virginal was advertised as a piece of painted furniture.

Metz enlisted Walter and Berta Burr and the three embarked on a three-year restoration, investigating construction materials and techniques and ferreting out the original from more recent. They found no original date or signature on the instrument, but based on the keyboard scroll (a decorative element unique to each builder), Denzil Wraight, an expert in Italian instruments of the late Renaissance and early Baroque, identified it as the work of Francesco Poggi. The prolific Poggi, who worked in Florence and died there in 1634, built both harpsichords and virginals, but only his virginals have survived. In fact, more Poggi virginals survive than those by any other builder, a testament to their sound and superior construction. With this discovery, 18 extant instruments by Poggi have been documented, all but three (including this one) in museum collections. Another Poggi virginal, signed and dated 1588, resides in the Tagliavini Collection in Bologna, Italy and features the exact same rose as Metz’s instrument. Based on this match and other internal data, Metz dates his instrument to c.1590.

While the instrument case and lid appear original, their decoration is not. Chemical analysis of the exterior paint revealed zinc white, an elemental pigment not available to artists until 1830. Additionally, beneath the soundboard an Italian inscription documents a prior restoration from 1891 in Grosseto, Italy. The current painting and cabriole stand likely date from that restoration. An X-ray of the lid showed no earlier painting beneath this 19th-century layer and it is possible that the instrument case left Poggi’s shop unadorned.

Typical of early Italian keyboards, this one features a cypress soundboard constructed from a single plank from a single tree. Cypress trees grow slowly and this tree had to have been ancient when harvested for the soundboard in the late 16th-century.

Over the course of its 400 years, this soundboard had collapsed downward and distorted under the string tension. A virginal differs from a harpsichord in that it has two bridges on the soundboard, increasing the load and downward pressure. Despite this damage, the restoration could not include removing this original soundboard, so Walter Burr began a three-year process of re-bracing and an almost daily wetting and drying. Upward pressure from new braces and the slow water treatment eventually leveled the soundboard. Burr also closed over 40 cracks in this single plank with cypress cleats. The superior sound and resonance of the instrument is due, in large part, to this tedious and careful restoration. Other parts were beyond repair. The original jacks, distorted with age, were replaced as were some sharp keys suffering from dry rot. The keyboard, though worn, was leveled and the original natural keys offer an almost organic unevenness from centuries of playing.

The instrument has been restrung following historical guidelines with the seven lowest notes in brass and the remainder in iron. Typical of 16th-century instruments, this virginal has a 50-note compass with a short octave C/E in the bass extending to f”’ in the treble. Unlike some of Poggi’s later instruments, it has no split sharps. For this recording, Dr. Metz chose to tune the virginal to 406 Hz=A in quarter-comma meantone.

Most modern listeners regard the virginal as a quieter and less advanced predecessor of the harpsichord. This misunderstanding does the instrument and its repertoire a disservice. It is better appreciated as a cousin to the harpsichord, much as the lute and guitar are related. Like the lute and guitar, the virginal and harpsichord share similar (but not identical) physical traits, employ similar (but not identical) sounding technologies, and were regularly used for similar musical purposes. Like the lute, the virginal enjoyed its heyday in the 16th-century but by the late 17th-century, the harpsichord had displaced it as the plucked keyboard instrument of choice.

Unlike the harpsichord, the virginal carries only one string for each pitch, offering an uncompromising clarity of attack and a sound sometimes described as “flute-like.” This particular instrument has a dark, bell-like mid-range with reedy bass and treble registers. Some observers note that the virginal mimics the lute’s sharp attack, round bloom and rapid decay. In fact, lutes and virginals often appear together in images of 16th-century music-making usually in ensembles or accompanying singers.

Unsurprisingly, the virginal and lute also shared repertoires, demonstrated by this recording which features music by or associated with William Tisdale. Taken from two manuscript collections, this music dates from the late 16th-century and represents a cross-section of the main repertoire of virginalists and lutenists of the day—somber and complex pavans, sprightly galliards and almans, bouncy corantos, and virtuosic variation sets on popular songs or ballad tunes. Only the absence of the contrapuntal fantasia prevents this recording from being fully representative of the Elizabethan keyboard and lute repertoire.

20 pieces assigned to Tisdale appear in The John Bull Manuscript, a motley of madrigals, consort music, and theatre songs. Pavans far and away dominate, with ten. Three galliards, two corantos, and five variation sets round out Tisdale’s work in the Bull Manuscript. Metz fills out this recording from the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book (FWVB) which holds the only other pieces ascribed to Tisdale

Next to nothing is known of Tisdale. Two William Tisdales lived in London in the late 16th-century. One died in 1603, the other in 1605. There may be a connection to the family of Francis Tregian, compiler of FWVB, but this remains conjectural.

Although Tisdale himself remains virtually anonymous, his compositions are in excellent musical company. Five pieces on this recording are ascribed to Tisdale, while others come from the pens of some of England’s most famous musicians including William Byrd (c. 1540–1623), John Dowland (1563–1626) and Thomas Morley (1557/8–1602). Although not well-known today, other musicians in this anthology held prestigious positions in London at the turn of the 17th-century, including William Randall (d. 1604?), organist and member of the Chapel Royal and John Marchant (fl. 1588–1611), likewise a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal but also Elizabeth’s virginal tutor. Their younger contemporary, Robert Johnson (c. 1583–1633) composed numerous songs for the theatre and served as lutenist to James I from 1604 until his death. Edward Johnson (fl. 1572–1601) had a long career as composer and performer, appearing before Elizabeth in the famed entertainment at Kenilworth Castle in 1575.

In A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke (1597), Thomas Morley includes a description of the most popular and significant musical forms of the day. The large number of pavans in the Tisdale repertoire suggests, and Morley confirms, that this serious dance stood second only to the fantasie in significance. Morley describes the pavan as a slow dance in three repeated strains featuring loose imitative counterpoint. This framework allows considerable latitude as evidenced by the variety among the dozen pavans presented here. Morley explains that pavans were typically paired with quicker galliards, but the Tisdale collection links only the anonymous Passamezzo Pavan and Passamezzo Galliard. Like the late 16th-century pavan, the galliard featured imitative counterpoint, but its relative speed more often demanded momentary imitative “points” than expansive contrapuntal phrases.

Tisdale’s works include not only settings of John Dowland’s famed Lachrimae Pavan but the even more famous Susanne un Jour, an account of the Biblical story of Susanna and a pack of leering elders. Tisdale drew on Orlando de Lasso’s 1567 setting, which appears in numerous versions for lute and keyboard. Other titled pieces in the Tisdale collection—The Hunt’s Up, Paul’s Wharf, and My Desire—likely originated as ballad tunes but survived principally as foundations for divisions or variations.

Neither of the two corantos in the collection is titled, but both are ascribed to Tisdale. These are Italianate dances rather than the more rhythmically complex and modern French courante of the era. The only almand on this recording, likewise credited to Tisdale, appears in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book.

— Dr. Jeffery Noonan