A Native Hill

Gavin Bryars composer

Wendell Berry author

The Crossing | Donald Nally conductor

Navona Records presents A NATIVE HILL from Philadelphia’s professional chamber choir, The Crossing. This monumental unaccompanied work is the result of a collaboration with composer Gavin Bryars, whose previous work for The Crossing won them their first of two recent Grammy awards. With intimate knowledge of the individual voices and art of each singer, Bryars composed A NATIVE HILL to capitalize on the group’s unique sound, personality, and esprit de corps. A NATIVE HILL is based on American author and environmentalist Wendell Berry’s 1968 essay of the same name, which examines bucolic elements of rural life, suffused with deeper metaphysical and political implications. The new album is full of rich, complex vocal textures, dense chromatic clusters, and moments of profound simplicity, offering an opportunity to reflect on life’s timeless questions.

Listen

Stream/Buy

Choose your platform

Track Listing & Credits

| # | Title | Composer | Performer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | A Native Hill: No. 1, The Sense of the Past | Gavin Bryars | The Crossing | Donald Nally, conductor | 6:40 |

| 02 | A Native Hill: No. 2, The Path | Gavin Bryars | The Crossing | Donald Nally, conductor | 4:44 |

| 03 | A Native Hill: No. 3, Sea Level | Gavin Bryars | The Crossing | Donald Nally, conductor | 5:08 |

| 04 | A Native Hill: No. 4, The Pool | Gavin Bryars | The Crossing | Donald Nally, conductor | 3:18 |

| 05 | A Native Hill: No. 5, The Road | Gavin Bryars | The Crossing | Donald Nally, conductor | 8:15 |

| 06 | A Native Hill: No. 6, The Music of Streams | Gavin Bryars | The Crossing | Donald Nally, conductor | 8:21 |

| 07 | A Native Hill: No. 7, Questions | Gavin Bryars | The Crossing | Donald Nally, conductor | 5:15 |

| 08 | A Native Hill: No. 8, Top Soil | Gavin Bryars | The Crossing | Donald Nally, conductor | 4:27 |

| 09 | A Native Hill: No. 9, The Hill | Gavin Bryars | The Crossing | Donald Nally, conductor | 3:36 |

| 10 | A Native Hill: No. 10, Animals and Birds | Gavin Bryars | The Crossing | Donald Nally, conductor | 4:15 |

| 11 | A Native Hill: No. 11, Shadow | Gavin Bryars | The Crossing | Donald Nally, conductor | 5:02 |

| 12 | A Native Hill: No. 12, At Peace | Gavin Bryars | The Crossing | Donald Nally, conductor | 9:36 |

The Crossing

Jessica Beebe . Kelly Ann Bixby . Katy Avery . Nathaniel Barnett . Karen Blanchard . Steven Bradshaw 1 2 . Colin Dill . Micah Dingler . Ryan Fleming . Joanna Gates . Dimitri German . Dominic German . Steven Hyder . Heidi Kurtz . Maren Montalbano 2 . Rebecca Myers . Becky Oehlers . James Reese . Daniel Schwartz . Rebecca Siler . Julie Snyder . Daniel Spratlan . Elisa Sutherland . Daniel Taylor 1

1 soloist on Mvt. iv

2 soloist on Mvt. xi

Gavin Bryars music

Wendell Berry words

Donald Nally Conductor

Kevin Vondrak Assistant Conductor

John Grecia Keyboards

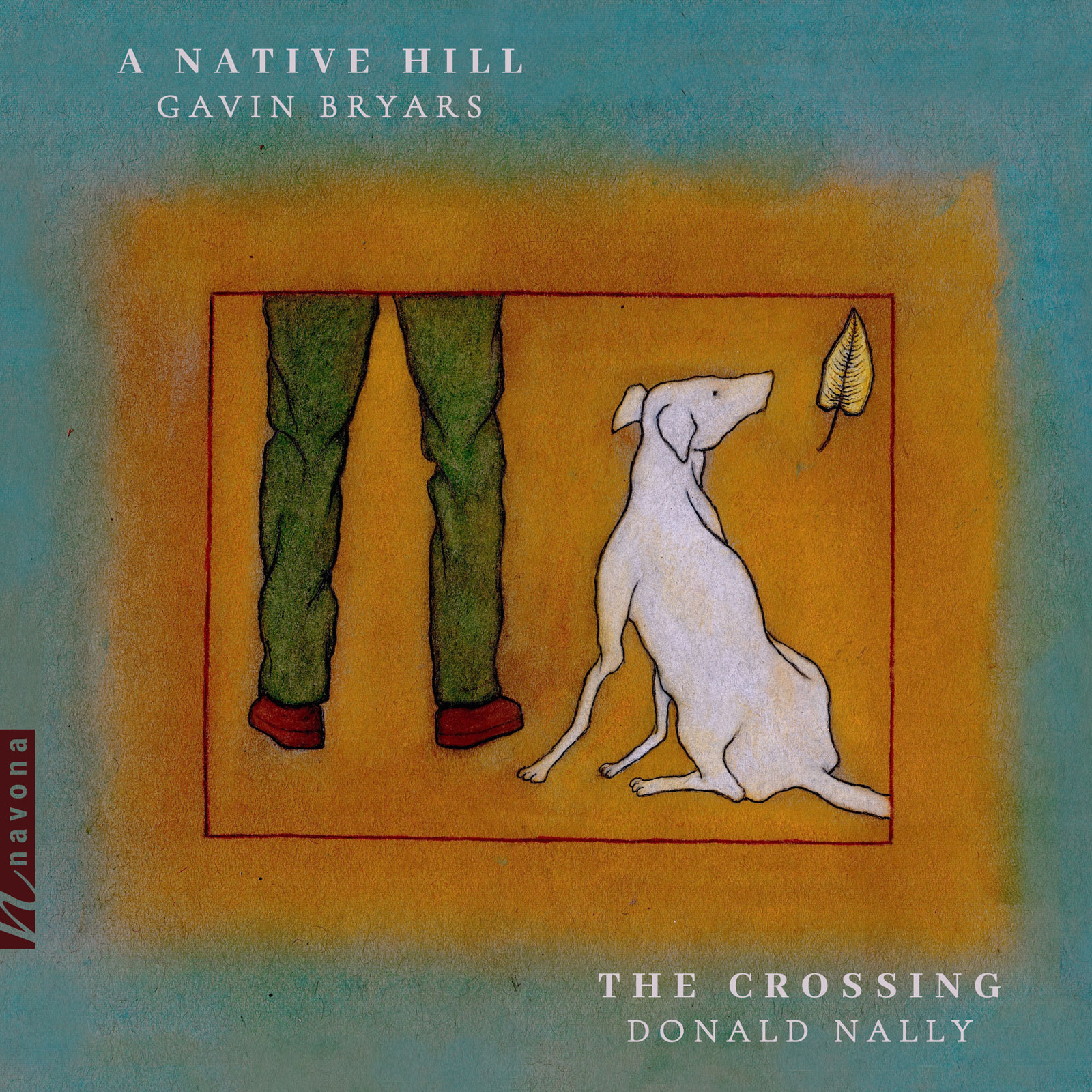

Album artwork by Steven Bradshaw stevenbradshawart.com

A NATIVE HILL was recorded October 8-11, 2019 at St. Peter’s Church in the Great Valley, Malvern PA

Recording Producers Paul Vazquez, Donald Nally, and Kevin Vondrak

Recording Engineers Paul Vazquez and Dante Portella

Editing, Mixing & Mastering Paul Vazquez

Production assistance Logan Henke

THE RECORDING OF A NATIVE HILL IS MADE POSSIBLE through the generous gift of a long-time supporter of The Crossing.

WE ARE GRATEFUL FOR:

Our artists, composers, audience, friends, and supporters;

Gavin Bryars;

Jack Shoemaker at Counterpoint Press;

Tony Creamer;

the staff and congregation at our home, The Presbyterian Church of Chestnut Hill;

those who opened their homes to our artists during the recording of A Native Hill: Rev. Cindy Jarvis, David and Rebecca Thornburgh, Jeff and Liz Podraza, Beth Vaccaro and Landon Jones, Rebecca Siler, Corbin Abernathy and Andrew Beck, David Newmann and Laura Ward.

THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS OF THE CROSSING

Kelly Ann Bixby

Phil Cooke

Micah Dingler

Shawn Felton

Tuomi Forrest – Vice President

Mary D. Hangley

Lisa Husseini

Cynthia A. Jarvis

Mary Kinder Loiselle

Michael M. Meloy

Donald Nally

Eric Owens

Pam Prior – Treasurer

Andrew Quint

James Reese

Kim Shiley – President

Carol Loeb Shloss – Secretary

John Slattery

Elizabeth Van de Water

THE STAFF OF THE CROSSING

Jonathan Bradley, executive director

Shannon McMahon, operations manager

Kevin Vondrak, assistant conductor & artistic associate

Paul Vazquez, sound designer

Katie Feeney, grant manager

Elizabeth Dugan, bookkeeper

Ryan Strand, administrative assistant

The Crossing is represented by Alliance Artist Management

www.allianceartistmanagement.com

COME. HEAR. NOW.

www.crossingchoir.org

Executive Producer Bob Lord

General Manager of Audio & Sessions Jan Košulič

Audio Director Lucas Paquette

Executive A&R Sam Renshaw

A&R Director Brandon MacNeil

VP, Design & Marketing Brett Picknell

Art Director Ryan Harrison

Design Edward A. Fleming

Publicity Patrick Niland, Sara Warner

Artist Information

The Crossing

The Crossing is a Grammy-winning professional chamber choir conducted by Donald Nally and dedicated to performing new music. It is committed to working with creative teams to make and record new, substantial works for choir that explore and expand ways of writing for choir, singing in choir, and listening to music for choir. Many of its nearly 150 commissioned premieres address social, environmental, and political issues.

Donald Nally

Donald Nally collaborates with creative artists, leading orchestras, and art museums to make new works for choir that address social and environmental issues. He has commissioned over 180 works and, with The Crossing, has 29 recordings, with two Grammy Awards and eight nominations. Nally has served as chorus master at the Lyric Opera of Chicago, Welsh National Opera, Opera Philadelphia, and the Spoleto Festival in Italy.

Gavin Bryars

Gavin Bryars (b. 1943) studied philosophy but became a jazz bassist and pioneer of free improvisation with Derek Bailey and Tony Oxley. Early iconic pieces The Sinking of the Titanic and Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet achieved great popular success.

Notes

music by Gavin Bryars (b. 1943)

words by Wendell Berry (b. 1934)

Composed as a gift for The Crossing; dedicated to Cassia Bryars-Rockey; In memoriam Julian Rockey.

First performance of movements 1-5:

14 December 2018

The Crossing

Donald Nally, conductor

Church of the Holy Trinity, Rittenhouse Square

Philadelphia PA

First complete performance

13 October 2019

The Crossing

Donald Nally, conductor

The Presbyterian Church of Chestnut Hill

Philadelphia PA

a note from the composer:

Following the success of our previous collaboration, I composed a substantial new a cappella work for The Crossing as a gift to the choir. It draws on our close working relationship and the personal friendships that have developed between us as well as my intimate knowledge of the singers’ individual characteristics, and there are solo parts written specifically for particular voices.

The piece is in twelve sections, setting extracts from the American writer Wendell Berry’s 1968 essay “A Native Hill.” Although at first appearance pastoral, Berry’s descriptions of the minutiae of his rural existence have a profound metaphysical and even political force. He has been called, a little simplistically perhaps, a modern-day Thoreau, although here his visionary prose has something of the mysticism of the text for my previous work with The Crossing when I set Thomas Traherne.

Quite coincidentally, I finished the piece on August 29th, the day my granddaughter Cassia was born, and I had worked on it, on and off, for nine months – the whole period of my daughter Orlanda’s pregnancy; and Cassia’s father, Orlanda’s partner Julian, had died suddenly half way through.

Completing the work in Canada throughout the summer was an intense experience: I had Orlanda’s situation always in mind ever since I left England in mid-June. In addition, I worked on the piece with a care and scrutiny beyond anything I have done before. Generally I compose very quickly, though usually after a period of reflection and study, often around questions of text while being mindful of the need to deliver. But here I did not set myself a specific deadline, and the result of this was that the energy I would normally have put into the speed of writing was diverted into detail and concentration.

This had already shown itself in the fourth section, The Pool, where the tenor solo voice is accompanied by complex textures involving extreme, though very quiet, harmonic colouring by groups of solo voices. My knowledge of the choir’s ability to rise to these challenges also encouraged me to experiment with background humming and whistling by pairs of solo voices in the tenth section, Animals and Birds. And I decided to open the last part, At Peace, with all 24 voices having completely independent and unconnected notes to make a chromatic cluster out of which cleaner harmonies could come into focus and melodic movement could be revealed. This dense covering reappears to a greater and lesser extent throughout the movement, with its eventual evaporation allowing the sense of being at peace to emerge. But, at the same time, there are also many moments of simple, church-like music. And this combination of the apparently traditional and deceptive complex comes about through a close reading of the text and reflects a deep respect for Wendell Berry’s beautiful prose.

— Gavin Bryars, 14 September 2019, Biarritz, France

Texts

–from the essay A Native Hill (1968).

© 2002 by Wendell Berry, from The Art of the Commonplace: The Agrarian Essays. Reprinted by permission of Counterpoint Press.