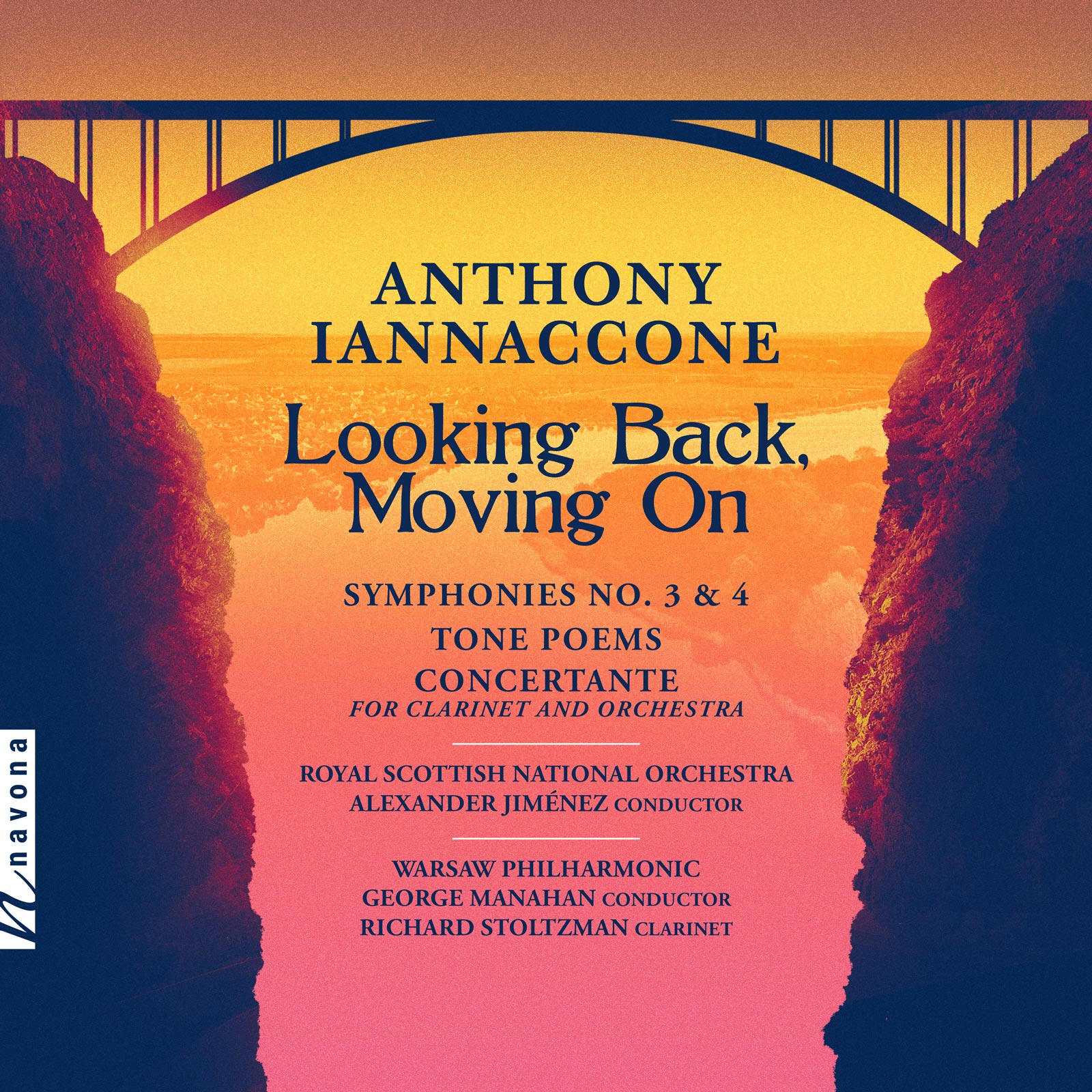

Looking Back, Moving On

Anthony Iannaccone composer

Royal Scottish National Orchestra | Alexander Jiménez conductor

Warsaw Philharmonic | George Manahan conductor

Richard Stoltzman clarinet

Contemporary symphonic music tends to fall into either one of two categories: hopelessly cerebral concert hall material that is difficult (if not impossible) to understand – or background music for motion pictures. Neither classification would be much to the liking of New York native Anthony Iannaccone, who sets out to prove that one can have the best of both worlds on LOOKING BACK, MOVING ON. Both his third and fourth symphonies make a strong case: spirited, organically structured, and imaginative, they are formidable displays of American verve. The Concertante for Clarinet and Orchestra, more subtle but no less energetic, drives home the point.

Listen

Stream/Buy

Choose your platform

...as impressive and cinematic as one might wish...

I recommend this release with enthusiasm.

...unmissable American symphonic gems with strength and integrity.

Track Listing & Credits

| # | Title | Composer | Performer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DISC 1 | ||||

| 01 | Night Rivers, Symphony No.3 (1992) | Anthony Iannaccone | Royal Scottish National Orchestra | Alexander Jiménez, conductor | 20:24 |

| 02 | Bridges, Symphony No.4 (2019): I. Bold Advance, Heavy Toll: A Rhine Bridge Too Far at Arnhem | Anthony Iannaccone | Royal Scottish National Orchestra | Alexander Jiménez, conductor | 12:22 |

| 03 | Bridges, Symphony No.4 (2019): II. Imagination and Endurance: Roebling’s Dream-Bridge Grows in Brooklyn | Anthony Iannaccone | Royal Scottish National Orchestra | Alexander Jiménez, conductor | 8:19 |

| 04 | Bridges, Symphony No.4 (2019): III. Strong Steel Emblems Vault the Channel: the “Verrazano” | Anthony Iannaccone | Royal Scottish National Orchestra | Alexander Jiménez, conductor | 5:44 |

| 05 | Waiting for Sunrise on the Sound (1998) | Anthony Iannaccone | Royal Scottish National Orchestra | Alexander Jiménez, conductor | 12:13 |

| DISC 2 | ||||

| 01 | Concertante for Clarinet and Orchestra (1994) | Anthony Iannaccone | Richard Stoltzman, clarinet; Warsaw Philharmonic | George Manahan, conductor | 15:39 |

| 02 | From Time to Time, Fantasias on Two Appalachian Folksongs (2000): I. Once upon a Time: Crosscurrents Remembered | Anthony Iannaccone | Royal Scottish National Orchestra | Alexander Jiménez, conductor | 11:42 |

| 03 | From Time to Time, Fantasias on Two Appalachian Folksongs (2000): II. Moving Time: a Millennium Ride | Anthony Iannaccone | Royal Scottish National Orchestra | Alexander Jiménez, conductor | 4:07 |

All works on this album are available from Theodore Presser Company

Night Rivers (Symphony no. 3), Bridges (Symphony no 4), Waiting for Sunrise on the Sound, From Time to Time

Recorded June 21-23, 2022 at New Auditorium at the Glasgow Royal Concert Hall in Glasgow, United Kingdom

Producer Brad Michel

Engineer Hedd Morfett-Jones

Assistant Engineer Sam McErlean

Editing & Mixing Brad Michel

Concertante for Clarinet and Orchestra

Producer Peter Kelly, Elliott Miles McKinley

Recording Andrzej Sasin, Andrzej Lupa, Zbigniew Fijalkowski

Editing Aneta Michalczyk-Falana

Mastering Jonathan Wyner, M Works Mastering

Executive Producer Bob Lord

A&R Director Brandon MacNeil

A&R Chris Robinson

VP of Production Jan Košulič

Production Director Levi Brown

Audio Director Lucas Paquette

Production Assistant Martina Watzková

VP, Design & Marketing Brett Picknell

Art Director Ryan Harrison

Design Edward A. Fleming, Morgan Hauber

Publicity Patrick Niland, Aidan Curran

Artist Information

Anthony Iannaccone

Anthony Iannaccone (b. New York City, 1943) studied at the Manhattan School of Music and the Eastman School of Music. His principal teachers were Vittorio Giannini, Aaron Copland, and David Diamond. During the 1960's, he supported himself as a part-time teacher (Manhattan School of Music) and orchestral violinist. His catalog of approximately 50 published works includes four symphonies, smaller works for orchestra, several large works for chorus and orchestra, numerous chamber pieces, large works for wind ensemble, and several extended a cappella choral compositions.

Royal Scottish National Orchestra

Formed in 1891 as the Scottish Orchestra, the company became the Scottish National Orchestra in 1950, and was awarded Royal Patronage in 1977. Throughout its history, the Orchestra has played an integral part in Scotland’s musical life, including performing at the opening ceremony of the Scottish Parliament building in 2004. Many renowned conductors have contributed to its success, including George Szell, Sir John Barbirolli, Walter Susskind, Sir Alexander Gibson, Neeme Järvi, Walter Weller, Alexander Lazarev and Stéphane Denève.

Richard Stoltzman

Richard Stoltzman's virtuosity, technique, imagination, and communicative power have revolutionized the world of clarinet playing, opening up possibilities for the instrument that no one could have predicted. He was responsible for bringing the clarinet to the forefront as a solo instrument, and is still the world's foremost clarinetist. Stoltzman gave the first clarinet recitals in the histories of both the Hollywood Bowl and Carnegie Hall, and, in 1986, became the first wind player to be awarded the Avery Fisher Prize.

Alexander Jiménez

Alexander Jiménez is widely regarded as a gifted, dynamic, and versatile conductor, and a highly-respected educator. He served as president of the College Orchestra Directors Association from 2010 to 2012, and is a recipient of numerous teaching awards. As Professor of Conducting and Director of Orchestral Studies at Florida State University, he has developed one of the most important orchestral training programs in the United States.

George Manahan

George Manahan has served for more than a decade as Director of Orchestral Activities at the Manhattan School of Music. He is also Music Director of the American Composers Orchestra and the Portland Opera. He served as Music Director of the New York City Opera for 14 seasons and was hailed for his leadership of the orchestra.

Lucy Miller Murray

Lucy Miller Murray, Founder of Market Square Concerts, is author of Chamber Music: An Extensive Guide for Listeners published by Rowman & Littlefield. She is a regular program annotator for many chamber music series across the country, and has written notes for programs by such luminaries as Joshua Bell, Frederica von Stade, and the London Philharmonic.