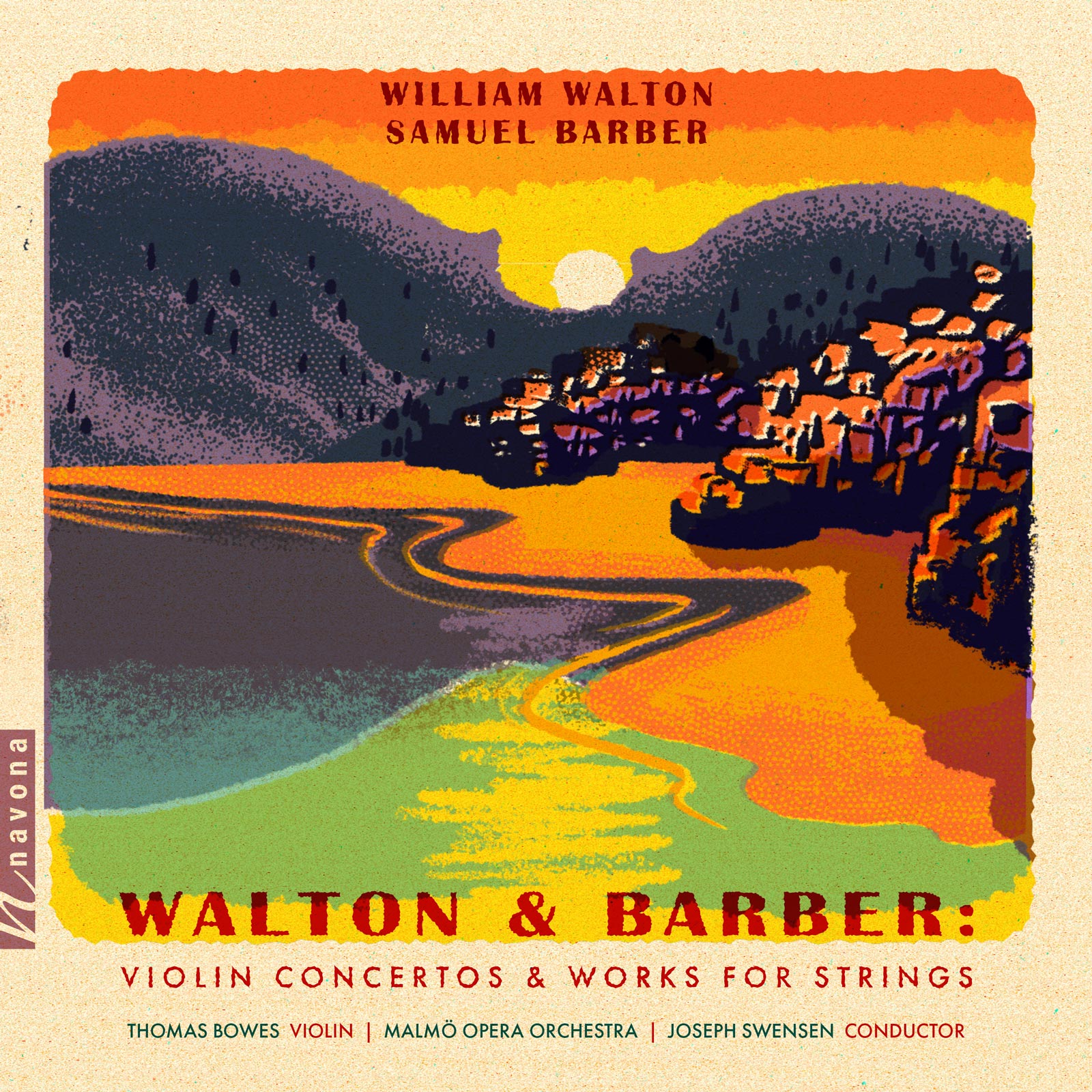

Walton & Barber

William Walton composer

Samuel Barber composer

Thomas Bowes violin

Malmö Opera Orchestra | Joseph Swensen conductor

WALTON & BARBER from famed British violinist Thomas Bowes celebrates the works of two early 20th century composers, William Walton and Samuel Barber. The album includes Walton’s Concerto for Violin and Orchestra and Two Pieces for Strings from Henry V, as well as Barber’s Concerto for Violin and Orchestra op. 14 and the touchstone Adagio for Strings op. 11. Throughout the album, Bowes’ breathtaking virtuosity is on full display. His playing, which has been characterized by Gramophone Magazine as “deeply human” and “unusually communicative,” teases out subtleties and rises to the challenge of the most technically-demanding passages. With the violin at centerstage, WALTON & BARBER brings the full power of the orchestra to bear.

Listen

Stream/Buy

Choose your platform

Track Listing & Credits

| # | Title | Composer | Performer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Concerto for Violin and Orchestra: I. Andante tranquillo | William Walton | Thomas Bowes, violin; Malmö Opera Orchestra | Joseph Swensen, conductor | 11:07 |

| 02 | Concerto for Violin and Orchestra: II. Presto capriccioso alla napolitana - Trio (Canzonetta) | William Walton | Thomas Bowes, violin; Malmö Opera Orchestra | Joseph Swensen, conductor | 6:21 |

| 03 | Concerto for Violin and Orchestra: III. Vivace | William Walton | Thomas Bowes, violin; Malmö Opera Orchestra | Joseph Swensen, conductor | 13:09 |

| 04 | Two Pieces for Strings from Henry V: I. Passacaglia: Death of Falstaff | William Walton | Thomas Bowes, violin; Malmö Opera Orchestra | Joseph Swensen, conductor | 3:09 |

| 05 | Two Pieces for Strings from Henry V: II. Touch Her Soft Lips and Part | William Walton | Thomas Bowes, violin; Malmö Opera Orchestra | Joseph Swensen, conductor | 1:27 |

| 06 | Concerto for Violin and Orchestra op. 14: I. Allegro | Samuel Barber | Thomas Bowes, violin; Malmö Opera Orchestra | Joseph Swensen, conductor | 9:44 |

| 07 | Concerto for Violin and Orchestra op. 14: II. Andante | Samuel Barber | Thomas Bowes, violin; Malmö Opera Orchestra | Joseph Swensen, conductor | 8:26 |

| 08 | Concerto for Violin and Orchestra op. 14: III. Presto in moto perpetuo | Samuel Barber | Thomas Bowes, violin; Malmö Opera Orchestra | Joseph Swensen, conductor | 3:45 |

| 09 | Adagio for String op. 11 | Samuel Barber | Thomas Bowes, violin; Malmö Opera Orchestra | Joseph Swensen, conductor | 8:53 |

Recorded March 8-12, 2010 at the Malmö Opera and Music Theatre in Malmö, Sweden

Producer Tony Harrison

Engineer Mike Hatch

Editing Stephen Frost

Executive Producer Bob Lord

A&R Director Brandon MacNeil

A&R Danielle Sullivan

VP of Production Jan Košulič

Audio Director Lucas Paquette

VP, Design & Marketing Brett Picknell

Art Director Ryan Harrison

Design Edward A. Fleming

Publicity Patrick Niland

Artist Information

Thomas Bowes

Thomas Bowes is one of the United Kingdom’s finest violinists. He is very active in the realm of cinema, and millions have heard him on the soundtracks of his 200+ film credits. Most recently he was featured as the solo violinist in Alexandre Desplat’s score for Guillermo del Toro’s award-winning stop-motion film Pinocchio.

Joseph Swensen

Joseph Swensen is Artistic Director of the NFM Leopoldinum Orchestra Wroclaw, Conductor Emeritus of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, and Principal Guest Conductor of the Orquesta Ciudad de Granada. He has previously served as Principal Guest Conductor & Artistic Adviser of the Orchestre de Chambre de Paris, Principal Conductor of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, and Principal Conductor of Malmö Opera. Swensen also enjoys a special relationship with the Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse of which he is the longest-serving guest conductor. A sought-after pedagogue, Swensen is also a visiting professor of conducting, violin, and chamber music at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland in Glasgow.

Notes

Videos

Thomas Bowes, violin and Malmö Opera Orchestra | Joseph Swensen, conductor performing Concerto for Violin and Orchestra by William Walton