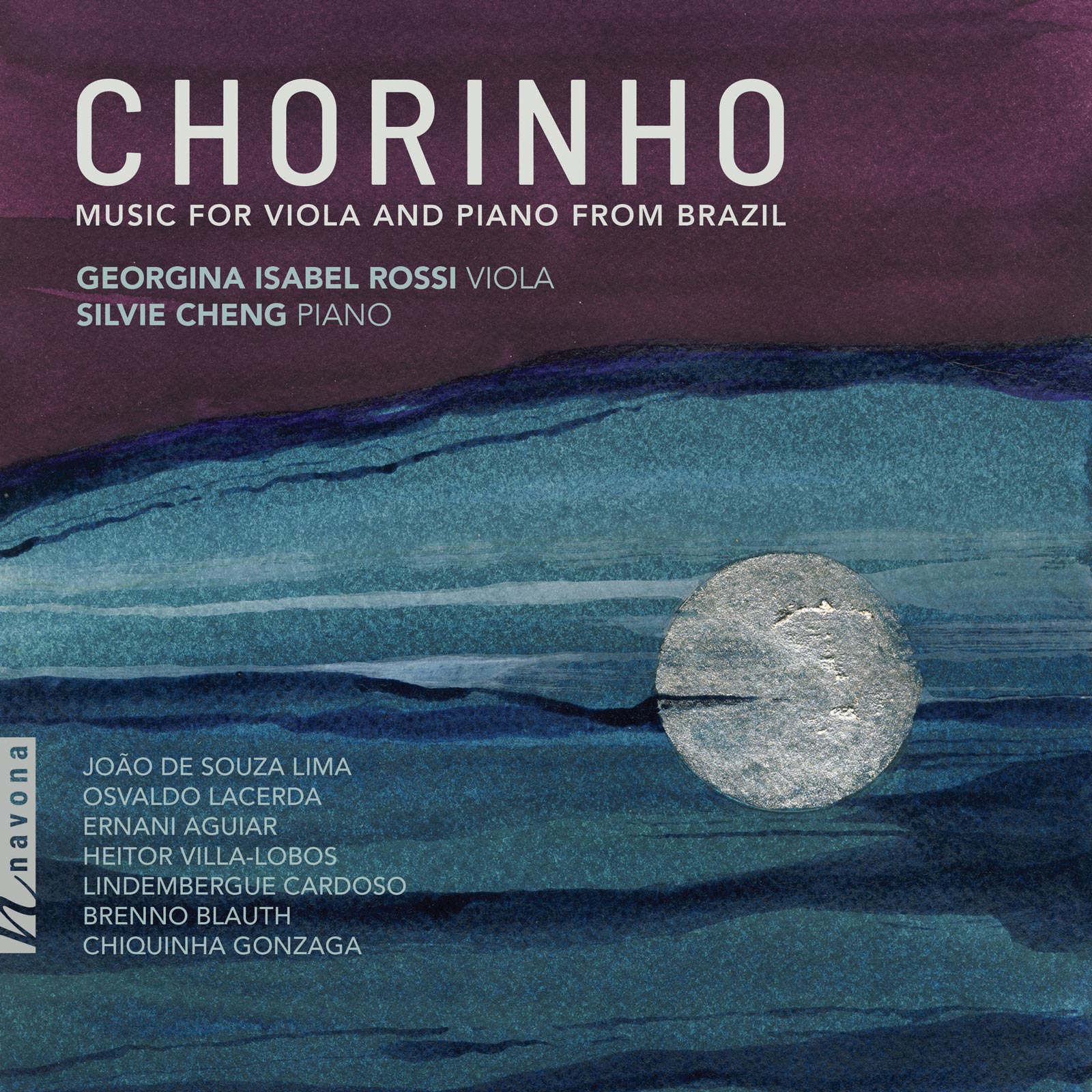

Chorinho

João de Souza Lima composer

Osvaldo Lacerda composer

Ernani Aguiar composer

Heitor Villa-Lobos composer

Lindembergue Cardoso composer

Brenno Blauth composer

Chiquinha Gonzaga composer

Georgina Isabel Rossi viola

Silvie Cheng piano

Navona Records is proud to present CHORINHO, the new album by violist Georgina Rossi and pianist Silvie Cheng. Saturated with Brazil’s rich musical heritage, CHORINHO presents a slew of under-recognized works for viola, including world-premiere recordings of works by João de Souza Lima, Lindembergue Cardoso, and Ernani Aguiar. A solo piano interlude honors Heitor Villa-Lobos, the titan of Brazil’s 20th century musical scene. The concluding track, an arrangement of Chiquinha Gonzaga’s song Lua Branca by the two soloists themselves, hangs over the collection like a light. Vibrant, soulful, and expressive, CHORINHO offers a spectacular glimpse into a little-known area of Brazilian contemporary music.

Listen

Stream/Buy

Choose your platform

"...consistently finessed eloquence of the highest sort."

Track Listing & Credits

| # | Title | Composer | Performer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Chorinho for viola and piano | João de Souza Lima | Georgina Isabel Rossi, viola; Silvie Cheng, piano | 7:09 |

| 02 | Appassionato, Cantilena, e Toccata for viola and piano: I. Appassionato | Osvaldo Lacerda | Georgina Isabel Rossi, viola; Silvie Cheng, piano | 5:06 |

| 03 | Appassionato, Cantilena, e Toccata for viola and piano: II. Cantilena | Osvaldo Lacerda | Georgina Isabel Rossi, viola; Silvie Cheng, piano | 5:09 |

| 04 | Appassionato, Cantilena, e Toccata for viola and piano: III. Toccata | Osvaldo Lacerda | Georgina Isabel Rossi, viola; Silvie Cheng, piano | 2:50 |

| 05 | Meloritmias: No.5 for solo viola: I. Ponteando | Ernani Aguiar | Georgina Isabel Rossi, viola | 3:08 |

| 06 | Meloritmias: No.5 for solo viola: II. Resposta ao bilhete do jogralrrapeixe | Ernani Aguiar | Georgina Isabel Rossi, viola | 4:07 |

| 07 | Meloritmias: No.5 for solo viola: III. Convite ao amigo Cristiano Ribeiro | Ernani Aguiar | Georgina Isabel Rossi, viola | 4:03 |

| 08 | Valsa da dor for solo piano | Heitor Villa-Lobos | Silvie Cheng, piano | 5:39 |

| 09 | Pequeno Estudio, op.78 for solo viola | Lindembergue Cardoso | Georgina Isabel Rossi, viola | 8:06 |

| 10 | Sonata for viola and piano: I. Dramático | Brenno Blauth | Georgina Isabel Rossi, viola; Silvie Cheng, piano | 7:20 |

| 11 | Sonata for viola and piano: II. Evocativo | Brenno Blauth | Georgina Isabel Rossi, viola; Silvie Cheng, piano | 7:12 |

| 12 | Sonata for viola and piano: III. Agitado | Brenno Blauth | Georgina Isabel Rossi, viola; Silvie Cheng, piano | 6:25 |

| 13 | Lua branca (from the operetta: O Forrobodó) | Chiquinha Gonzaga arr. Silvie Cheng, Georgina Rossi | Georgina Isabel Rossi, viola; Silvie Cheng, piano | 1:56 |

Recorded August 14–16, 2022 at Oktaven Audio in Mount Vernon NY

Recording Session Engineer, Mixing & Mastering Ryan Streber

Editing Ryan Streber, Edwin Huet

Liner Notes Georgina Rossi, Silvie Cheng

Editing Assistance Phil Rabovsky

Artwork Georgina Rossi

Photography Shervin Lainez, Tayla Nebesky

This album is dedicated to Roger Tapping, in memory of a wonderful teacher. Made possible with support from: The NYC Women’s Fund for Media, Music and Theatre by the City of New York Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment in association with The New York Foundation for the Arts.

Executive Producer Bob Lord

A&R Director Brandon MacNeil

A&R Danielle Sullivan

VP of Production Jan Košulič

Audio Director Lucas Paquette

VP, Design & Marketing Brett Picknell

Art Director Ryan Harrison

Design Edward A. Fleming

Publicity Patrick Niland

Digital Marketing Manager Brett Iannucci

Artist Information

Georgina Isabel Rossi

Chilean-American violist Georgina Isabel Rossi is on the faculty of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile’s Instituto de Música. Her first album, Mobili: Music for Viola and Piano from Chile (New Focus Recordings), was praised as “expertly played” (WQXR), “a startling new recording” (CVNC Journal), and was one of KDFC’s picks for “Favorite Albums of the Year.” She plays a Buenos Aires-made viola by Leonardo Anderi from 2014, and a bow by Christian Wilhelm Knopf.

Silvie Cheng

Chinese-Canadian pianist Silvie Cheng has performed in esteemed concert halls on five continents, from the California Center for the Arts to Brussels’ Flagey Hall, and the University of South Africa to Shanghai’s Poly Theatre. Close collaborations with composers of our time have led to over 50 world premieres since 2010, in such venues as Carnegie Hall, Cornell University, and the National Gallery of Canada. She tours extensively as the pianist of the Cheng² Duo and is a teaching-artist of The Orto Center at the Manhattan School of Music in New York City.

Notes

Violists can be guilty of relying too much on a short list of tried-and-true pieces. Here is just a slice of the viola repertoire available from one of the world’s most musically wealthy countries — all highly playable, terrifically rewarding, and much of it pointed out to us already in recordings by Brazil’s own Perez Dworecki and by Barbara Westphal. It is an honor and pleasure for us to offer first recordings of the rest. We do so with utmost care and in full awareness of the difference an easily accessed, quality recording can make to the story of a work of music and its composer. We hope this album will inspire many more interpretations and performances to come. The repertoire is certainly deserving.

— Georgina Isabel Rossi & Silvie Cheng