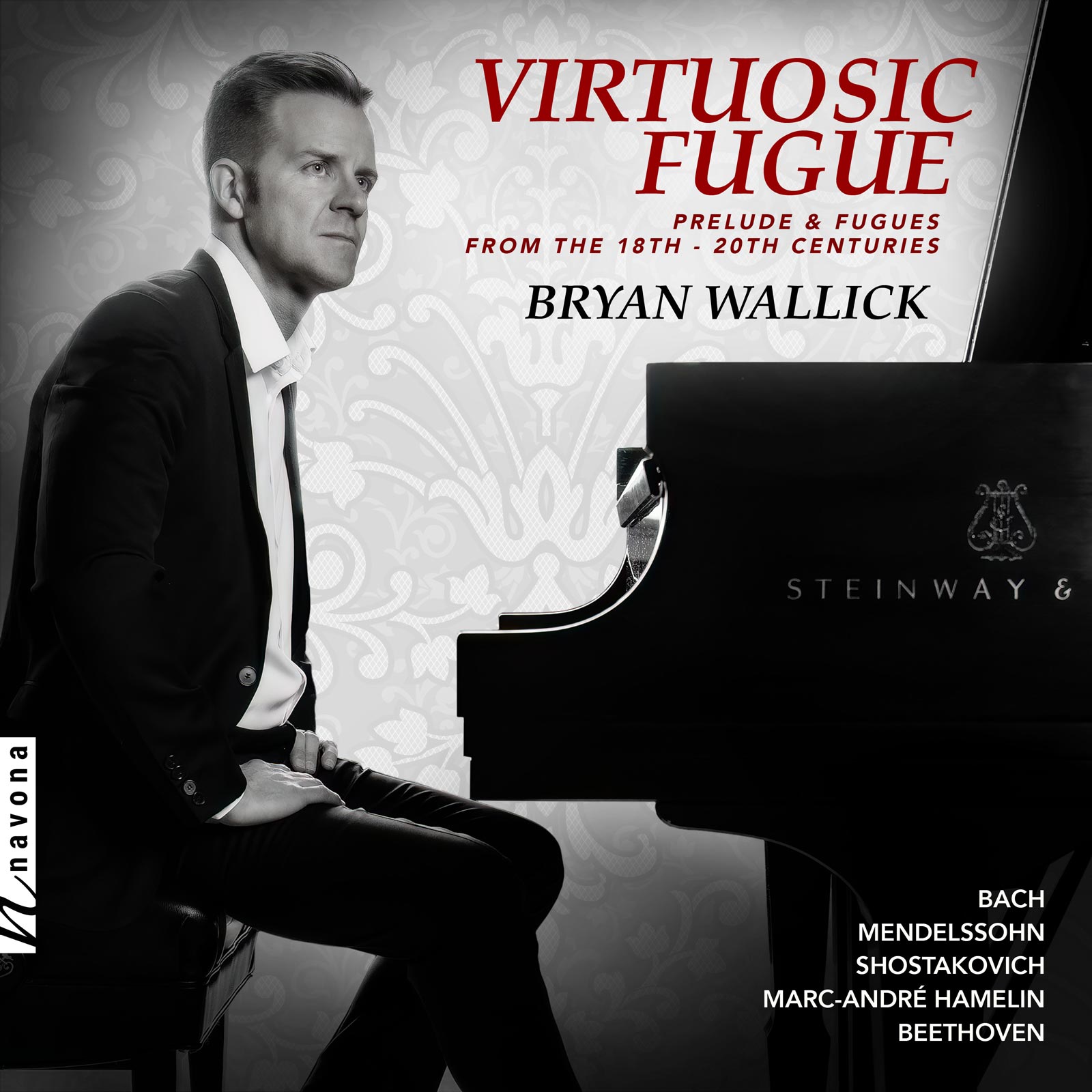

Virtuosic Fugue

Bryan Wallick piano

Johann Sebastian Bach composer

Felix Mendelssohn composer

Dmitri Shostakovich composer

Marc-André Hamelin composer

Ludwig van Beethoven composer

Good pianists are a dime a dozen, great pianists are one in a million. American virtuoso Bryan Wallick proves that he firmly belongs to the latter category on VIRTUOSIC FUGUE, a dazzling curation of music’s strictest and most challenging form, executed with a buttery, singing tone and ravishing technical bravura.

These fugues by J.S. Bach, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and Shostakovich challenge the pianist with the age-old dilemma of the form by performing them with a mesmerizingly light, precise touch, sparingly adding accent pedaling in highly strategic places. The result isn’t just a masterclass in expressive virtuosity; it’s also a mentally restorative, profoundly enjoyable listening experience.

Listen

Stream/Buy

Choose your platform

Track Listing & Credits

| # | Title | Composer | Performer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Toccata and Fugue in D Major BWV 912 | Johann Sebastian Bach | Bryan Wallick, piano | 10:33 |

| 02 | Prelude and Fugue in E minor Op. 35 No. 1 | Felix Mendelssohn | Bryan Wallick, piano | 8:34 |

| 03 | Prelude and Fugue in D minor Op. 87 No. 24 | Dmitri Shostakovich | Bryan Wallick, piano | 11:11 |

| 04 | Prelude and Fugue in A-flat minor (from 12 Études in all the minor keys, No. 12) | Marc-André Hamelin | Bryan Wallick, piano | 6:13 |

| 05 | Sonata No. 29 in B-flat major Op. 106 “Hammerklavier”: I. Allegro | Ludwig van Beethoven | Bryan Wallick, piano | 10:46 |

| 06 | Sonata No. 29 in B-flat major Op. 106 “Hammerklavier”: II. Scherzo: Assai vivace | Ludwig van Beethoven | Bryan Wallick, piano | 2:51 |

| 07 | Sonata No. 29 in B-flat major Op. 106 “Hammerklavier”: III. Adagio sostenuto: Appassionato e con molto sentiment | Ludwig van Beethoven | Bryan Wallick, piano | 15:38 |

| 08 | Sonata No. 29 in B-flat major Op. 106 “Hammerklavier”: IV. Introduzione: Largo-Fuga: Allegro risoluto | Ludwig van Beethoven | Bryan Wallick, piano | 12:15 |

Recorded December 14, 2022, February 1-2, 2023, at Organ Recital Hall, Colorado State University in Fort Collins CO

Session Producer Bryan Wallick

Session Engineer James Doser

Piano Technician Justin Holcomb

Cover photo Shayne Hopkins

Mastering Melanie Montgomery

Executive Producer Bob Lord

A&R Director Brandon MacNeil

A&R Chris Robinson

VP of Production Jan Košulič

Audio Director Lucas Paquette

VP, Design & Marketing Brett Picknell

Art Director Ryan Harrison

Design Edward A. Fleming

Publicity Aidan Curran

Artist Information

Bryan Wallick

Bryan Wallick is gaining recognition as one of the great American virtuoso pianists of his generation. Gold medalist of the 1997 Vladimir Horowitz International Piano Competition in Kiev, he has performed throughout the United States, Europe, and Africa. Wallick made his New York recital debut in 1998 at Carnegie’s Weill Recital Hall and made his Wigmore Hall recital debut in London in 2003. He has also performed at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall with the London Sinfonietta and at the St. Martin-in-the-Fields Church with the London Soloist’s Chamber Orchestra.

Notes

Historically, the English term fugue originates from the Latin fuga, which is a related term for fugere (“to flee”) and fugare (“to chase”). Many composers used the term from the middle ages through the 17th century to describe canonic and eventually imitative works for two or more voices. By the time J.S. Bach began finalizing fugal form in the early 18th century, fugues generally would have been composed using the following principles:

A fugue describes a very structured and imitative work that begins with a brief subject on one instrument or voice which is answered (or chased, fugare) by another voice, repeating the subject in the dominant key. These two voices will soon be accompanied by a third voice in the bass, which restates the subject in the original tonic key. Fourth and fifth voices (or more) can be added later in different capacities, but the musical interplay in a fugue usually revolves around three or four voices that continually repeat the opening statement with a variety of compositional variations.

Typical modifications which can be applied to opening fugal statements include inversion (playing the theme upside down), retrograde (playing the theme backward), retrograde-inversion (playing the theme upside down and backward), diminution (reducing the rhythmic values of the subject), and augmentation (increasing the rhythmic values). Counter-subjects or second subjects may be introduced and are designed to complement and contrast the opening subject. False entrances (incomplete statements) can be used in building musical tension and are often used throughout episodes, which are transitory sections where the composer can modulate and explore different keys. Stretto is a device often used near the conclusion of a fugue, where several voices present the fugue subjects in short succession, with all voices making their entrance before the previous statement has finished, building climatic tension to conclude the fugue.

Composers use all of these devices to showcase different expressions with which the subject could be infused. And while the fugue is perhaps the strictest form of composition, these devices were originally designed by composers so they could improvise on the opening subject. There should be an improvisatory freedom permeating throughout all of these structures and devices.

I intend my collection of works in VIRTUOSIC FUGUE to pay homage to the real “father” of the modern fugue, Johann Sebastian Bach. He is the overwhelming inspiration for all of the pieces on this disc, and my program notes are limited in scope, not to analyze the works themselves, but to mostly highlight the relationship each composer had with Bach and his music.

— Bryan Wallick