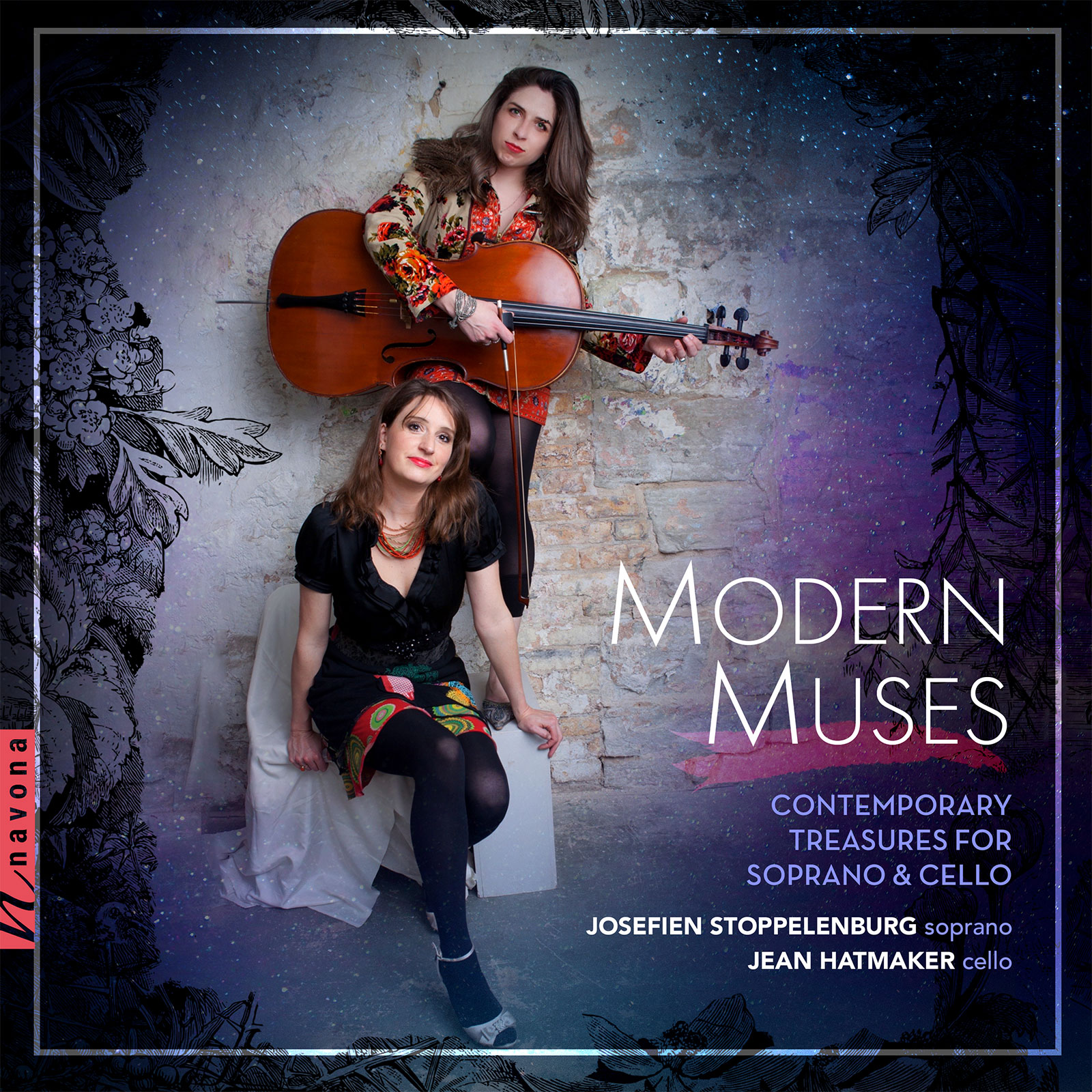

Modern Muses

Josefien Stoppelenburg soprano

Jean Hatmaker cello

MODERN MUSES is an entirely new presentation of captivating music in its first commercial recording and release, showcasing works composed by women and works representing female perspective. Inspired by Greek and Roman mythology, Josefien Stoppelenburg’s arresting soprano is juxtaposed with Jean Hatmaker’s poetic cello in this recording, fostering a rich musical dichotomy that blends together in a refreshingly powerful way. Join these two female performers on a journey through exotic soundscapes and empowering instrumentation in this diverse assortment of modern music.

Listen

Stream/Buy

Choose your platform

Track Listing & Credits

| # | Title | Composer | Performer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Alba | Alexis Bacon | Josefien Stoppelenburg, soprano; Jean Hatmaker, cello | 6:48 |

| 02 | Ionic | Willem Stoppelenburg | Josefien Stoppelenburg, soprano; Jean Hatmaker, cello | 4:38 |

| 03 | Ah! Sunflower | Ronald Tremain | Josefien Stoppelenburg, soprano; Jean Hatmaker, cello | 1:41 |

| 04 | Sick Rose | Ronald Tremain | Josefien Stoppelenburg, soprano; Jean Hatmaker, cello | 1:42 |

| 05 | Ahimsa | Jean Hatmaker | Jean Hatmaker, cello | 5:25 |

| 06 | This is Just to Say | Bernd Johannes Wolf | Josefien Stoppelenburg, soprano; Jean Hatmaker, cello | 1:50 |

| 07 | Olga | Willem Stoppelenburg | Josefien Stoppelenburg, soprano; Jean Hatmaker, cello | 7:37 |

| 08 | Moon Sister | Paul Ayres | Josefien Stoppelenburg, soprano; Jean Hatmaker, cello | 1:25 |

| 09 | Il Lamento Di Fedra | Antonio Bibalo | Josefien Stoppelenburg, soprano; Jean Hatmaker, cello | 13:54 |

| 10 | Dawn | Stacy Garrop | Josefien Stoppelenburg, soprano; Jean Hatmaker, cello | 2:49 |

| 11 | Vocalise | Katherine Dudney | Josefien Stoppelenburg, soprano; Jean Hatmaker, cello | 4:25 |

| 12 | Canción De Cuna | Adrián A. Cuello Piraquibis | Josefien Stoppelenburg, soprano; Jean Hatmaker, cello | 2:35 |

Recorded October 2020 at Grace Lutheran Church in River Forest IL

Recording Session Producer & Engineer Yuri Lysoivanov

Cover photo Sally Blood

General Manager of Audio & Sessions Jan Košulič

Audio Director Lucas Paquette

Executive Producer Bob Lord

Executive A&R Sam Renshaw

A&R Director Brandon MacNeil

A&R Morgan Santos

VP, Design & Marketing Brett Picknell

Art Director Ryan Harrison

Design Edward A. Fleming

Publicity Patrick Niland, Sara Warner

Artist Information

Josefien Stoppelenburg

Josefien Stoppelenburg is best known for her dazzling vocal agility and her passionate and insightful interpretations. She performed all over the United States and Europe and sang for the Dutch Royal Family on several occasions.

Jean Hatmaker

Jean Hatmaker is a founding member of the Kontras Quartet, the internationally acclaimed quartet-in-residence at Grace Lutheran Church of River Forest IL. Known for their well-crafted performances, diverse programming, and accessible audience relations, Kontras Quartet has brought their message of inclusivity to concerts across the United States, Europe, and Africa. In addition to classical concerts, Kontras Quartet performs with the bluegrass trio the Kruger Brothers, with whom they have appeared at festivals internationally.

Notes

Welcome to an intimate gathering of friends: Josefien, Jean…and now you. Together the three of you will navigate a fascinating journey through some rare and exotic musical landscapes and meet some new friends along the way. If you don’t know what to expect, it’s not a surprise. Not much in the way of works for soprano and cello duo has been recorded, or even composed. But here you will find a refreshingly modern sound with captivating music that is powerful and cathartic, none of which has been commercially recorded or released.

Why “Modern Muses”? This is certainly a modern recording. Completed in 2021, the collection’s oldest works were written in 1987, and several of them are from the past few years. Muses derive from Greek and Roman mythology, and you will find ancient and mythological themes among these works. These were goddesses who inspired, and a number of the works here are composed by women or taken from the perspective of a woman—the two female performers have been the catalyst in several of these works as well. Your takeaway: music on universal themes and human experiences, told with a modern voice in an intimate instrumentation.

A broad palette of expression awaits your ears. The journey includes works of secret sensuality, like Bacon’s Alba, a medieval song set in the Occitan language about clandestine lovers who meet in the night and have to flee at the break of dawn, and like Ayres’s Moon Sister, a crystalline setting of a translation/interpretation of Sappho’s translucent imagery. Tremain’s two Blake songs, Ah! Sunflower and The Sick Rose, project a sense of melancholy upon his floral subjects. With Ionic (Stoppelenburg / Cavafy) we feel the nostalgia of the ancient Greek gods for their golden age. There are also some dark passages on this journey: Stoppelenburg’s Olga and Bibalo’s Il Lamento di Fedra both portray women driven to and beyond the brink of sanity, while Hatmaker’s ahimsa for solo cello treats the internal struggle to be good, both to yourself and others. The mood lightens with Wolf’s setting of William Carlos Williams’s This Is Just to Say, and is filled with awe in Garrop’s depiction of Paul Dunbar’s Dawn. The recording ends with two works that radiate tenderness: after an initial stormy introduction, Dudney’s Vocalise oozes warmth, and Cuello Piraquibis’s Canción de Cuna sends us off with a lullaby.

— Ted Hatmaker